Using Existing Doctrine to Understand and Secure the Information Environment

Every soldier scrolling through social media on their phone is like an intelligence analyst, sifting through multiple sources of information in order to discern reality. Because of the similarity, leaders must work to protect themselves and their units from external influence operations. They must understand the threat, understand the environment, and be empowered to respond. This article explains the first two and explains how leaders can take Army tools designed to help intelligence analysts dispassionately analyze information and use the tools to defend themselves and those they lead from threats in the information environment.

There is ample evidence that external actors are seeking to influence military personnel. Russia actively works to exploit divides in society and undermine our nation from within. In some cases, service members are the specific targets of these operations. Social media is also a valuable recruiting tool for terrorist organizations: ISIS used it to recruit an estimated 40,000 foreign nationals. Using the same tactics, domestic right wing extremist organizations are using social media to recruit active duty soldiers. That campaign has been an evident success: of those arrested after the January 6th insurrection at the capitol with ties to extremist militant groups, one third had military background. Secretary Austin’s stand down to discuss extremism is an excellent step to deal with this issue, but it fails to address the underlying vulnerability in the information environment.

This need has been identified by other experts in the field. Last November, Col. Stephen Hamilton and Dr. Jan Kallberg, both with the Army Cyber Institute, argued that the Army must implement “cognitive force protection” to “train and enable the individual to see the demarcation between truth and disinformation.” In the wake of the January 6th insurrection, Peter Singer and Eric Johnson, highlighted the urgent necessity of implementing digital literacy training to protect the military in an increasingly complex information environment. As the Army develops service-wide solutions, leaders need to take their own immediate steps to protect their subordinates.

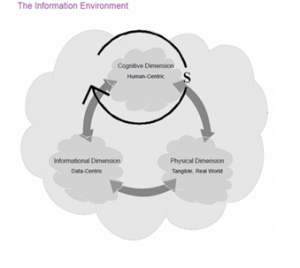

First, leaders need to understand the basics of what the information environment is and how it works. JP 3-13 defines the information environment as “the aggregate of individuals, organizations, and systems that collect, process, disseminate, or act on information.” Department of Defense doctrine further breaks the environment down into three dimensions: the Information Dimension (the actual information being communicated), the Physical Dimension (the means by which information moves, like social media, books, newspapers, etc.), and the Cognitive Dimension (the minds of those who interact with the information). (JP 3-13)

Given the sheer size of the information environment and the importance of allowing soldiers access to a wide variety of perspectives, it is not feasible, nor desirable, to protect soldiers by limiting their access to information. This means that the solution must come within the cognitive dimension. This dimension is affected by a complex array of internal variables: “individual and cultural beliefs, norms, vulnerabilities, motivations, emotions, experiences, morals, education, mental health, identities, and ideologies” (JP 3-13). For leaders to help subordinates discern truth from falsehood, they also need to help their subordinates understand how individual factors shape not only the consumption of information, but how that information is generated in the first place.

The intelligence community has been focused on this issue for years. Entire books have been written about the intersection of intelligence analysis and critical thinking. A summary of this body of knowledge is contained in “Cognitive Considerations for Intelligence Analysts,” a twelve page appendix in ATP 2-33.4, Intelligence Analysis. Again, think of the soldier as an intelligence analyst. The ability of an intelligence analyst to be successful depends on their ability to draw accurate analytical conclusions. If the analyst cannot think critically or is blinded by their individual bias, they may draw inaccurate conclusions, potentially costing lives or resulting in mission failure. The individual soldier, as they assess the world around them through the information environment, is also apt to draw faulty conclusions if they use faulty analytical skills. Because of this, “Cognitive Considerations for Intelligence Analysts” has a crucial application to protecting the force in the information environment.

For leaders, this appendix provides a foundation of Army-approved information to help themselves and their unit make sense of the information around them and ensure that they are using sound reasoning to draw conclusions. The appendix provides a starting point for discussions about fifteen logical fallacies, four different types of biases, the eight elements of thought, and nine intellectual standards. These topics help anyone who is analyzing information to better critique both the source and how they think about the source. Both are essential to combat attempts to influence through bad information.

Of course, this is not a complete solution. Proper defense in the cognitive dimension requires also understanding how the physical and information dimensions function. For example, training should discuss how social media algorithms can reinforce bias and teach how to question the veracity of an online source, both of which are essential for critical thinking to be useful in fighting bad information. Soldiers also should also learn how both foreign and domestic threats use disinformation and influence tactics. For example, this Department of State publication on Russian disinformation operations can provide insight on a well-known foreign actor.

Despite these shortcomings, “Cognitive Considerations for Intelligence Analysts” and resources like it can serve as an immediately usable tool to protect the force from external influence. For first-line leaders, it can serve as a starting point for an officer professional development conversation or platoon discussion about the dangers of influence operations and how to avoid bias and logical fallacies in media consumption. On a higher level, leaders can integrate information from “Cognitive Considerations for Intelligence Analysts” with resources that address its shortcomings to craft a more comprehensive solution to protect the force.

While the modern information environment can seem daunting, leaders at all levels can benefit from work the Army has already completed. Our institutional knowledge is wide and can be creatively applied to solve new problems. “Cognitive Considerations for Intelligence Analysts” proves that fact and provides a way that leaders on all levels can work now to address an urgent issue and offer the force much-needed protection in the information environment.

———

2nd Lt. Robert Norwood is an Armor Officer with an extensive interest in the information environment. He is a Truman Scholar and a Leadership Fellow for the Center for Junior Officers.

Related Posts

Fighting as an Enabler Leader

(U.S. Army Photo by Cpl. Tomarius Roberts, courtesy of DVIDS)Enablers provide capabilities to commanders that they either do not have on their own or do not have in sufficient quantity …

Defeating the Drone – From JMRC’s “Skynet Platoon”

If you can be seen, you can be killed—and a $7 drone might be all it takes. JMRC’s Skynet Platoon discuss their TTPs to defeat the drone.

3 Deployments Before Captain: Reflections From Down Range

Deployments challenge junior officers beyond their primary duties, often demanding adaptability, wellness management, proactive leadership, and moral integrity maintenance.