Cultivating Culture

As the son of an immigrant from Zimbabwe, I have always been interested in how culture influences the way people think and how it is created. The former dean of Harvard Business School Clay Christensen states, “Culture. It is a word we hear extensively on a day-to-day basis, and many of us associate it with different things…it is common to describe culture as the visible elements of a working environment…but those [elements] are just artifacts of it [culture].” (1) Culture can be defined in context of a society, a company, a family, or even an individual. Culture is also integral to a military organization. It can be accidental or purposeful, temporary or permanent, absorbed or taught. Culture is dynamic.

Renowned professor Edgar Schein thinks of culture in terms of working together toward a common goal. Christensen develops Schein’s definition by stating that the ability to work together toward a common goal is not developed overnight. Rather, “it’s a creative process” and that process is difficult. (2) Culture, and its development, has often been at the forefront of my mind. During my time as a Platoon Leader and an Aide-de-Camp, I closely observed the way leaders from O-5 to O-10 either cultivated effective culture or allowed a toxic culture to develop and destroy their organizations. I have spent considerable time over the past several years contemplating systems to instill a healthy culture in the organizations I will lead, and more importantly how I will influence toxic cultures I join. This paper will narrow the academic definition of culture, discuss how culture is either built or manifests on its own, and analyze the pillars that I believe are necessary from my experience to build or change a culture.

Wooden’s Pyramid of Success Figure 1.1

Culture Defined and How to Cultivate It

Christensen argues that in a business and within a family, culture will be created either on its own or purposefully. “A culture can be built consciously or evolve inadvertently. If you want your family [business] to have a culture with a clear set of priorities for everyone to follow, then those priorities need to be proactively designed into the culture,” argues Christensen.(3) More bluntly, “Make no mistake: a culture happens, whether you want it to or not.” (4) He continues to point out that the development of culture must start early on, if you want to see behavior that aligns with the values of your company or family. Essentially, good, strong culture manifests only from stable, strong consistency.

Other authors provide similar, yet unique viewpoints regarding the role of culture in business. In his book, Principles, Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater Associates believes culture is so integral to the success of a company that he devotes one-third of his book to culture alone. He also provides significantly more detailed writing than Christensen of what organizational culture should look like. Diverging from Dalio’s detailed writing on culture, Christensen is content claiming that culture is extremely fluid and varies greatly based on numerous factors. He uses Pixar as an example. Upon reflection of the success Pixar’s culture has brought Pixar, Christensen notes, “That’s not to say that working together at Pixar is the way every company in the film industry should work.”(5) In other words, not only do aspects of culture change from organization to organization, but they should develop and change internally as well.

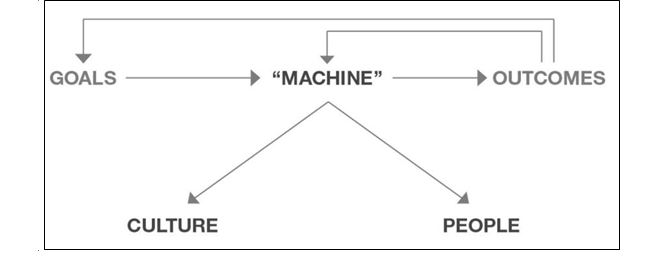

Principles’ extremely detailed account of culture tells a narrative that includes benchmarks and certain characteristics which must be present for success. Culture is not merely an important characteristic of a successful organization; it comprises half of what defines a great “machine” or organization. (6) “An organization is a machine consisting of two major parts,” writes Dalio, “culture and people. Nothing is more important or more difficult than to get the culture and people right” (See Figure 1.2)(7) With its focus on “People First”, this definition is highly applicable to the US Army. Dalio’s discussion of culture cannot be taken lightly. He goes as far as to claim:

Whatever successes we’ve had at Bridgewater were the result of doing that [culture and people] well – and whatever failures were due to our not doing it adequately. That might seem odd because, as a global macroeconomic investor, one might think that, above all else, I had to get the economics and investments right, which is true. But to do that, I needed to get the people and culture right first. (8)

To convey the weight Ray Dalio places on culture, he furthers his discussion of culture in many aspects, but four facets of culture stand out above the rest. First is the reciprocal nature of people and culture. Dalio writes, “Culture and people influence each other, because the people who make up an organization determine the kind of culture it has, and the culture of the organization determines the kinds of people who fit in.”(9) Most companies start with few people and grow to more employees, which means that a culture should be formed and inculcated by the founders of a company before employees are added because of the way the two groups impact each other.

Secondly, Dalio claims that a strong culture must possess and portray unchanging values and principles. “When there were five of us it was totally different than it was when we were five hundred, a thousand, and so on. As we grew, most everything changed beyond recognition, except for our core values and principles [culture].”(10) Prior to determining that fundamental values and principles cannot change, “For any group or organization to function well, its work principles must be aligned with its member’s life principles.”(11) Dalio’s company’s culture is based off his personal values. If he claims that the employees of his company must align with the principles of his company for the organization to work well, then, by default he is claiming that employee’s values which compose their concept of culture must align with his values that compose a concept of culture. If every value had to align, this would most assuredly cause major headaches; but Dalio caveats his statement by writing, “I don’t mean that they must align on everything, but I do mean that they must be aligned on the most important things, like the mission they’re on and how they will be there for each other.”(12)

Additionally, Dalio believes that a strong and healthy culture works to foster meaningful relationships. Without meaningful relationships, his final aspect of a strong culture, radical truth, would not be possible. (13) These types of relationships do not develop on their own, they must be worked for and intently built over time. Dalio states that meaningful relationships are not just important to culture, “they are invaluable for building and sustaining a culture of excellence.”(14)

Lastly, Dalio believes in fostering a practice of radical truth when constructing a strong culture. The sharing of truth, even failures and weaknesses, fosters trust, understanding, and respect. However, it also requires extreme vulnerability and the willingness to make mistakes. Without radical truth, meaningful relationships could not be possible, and vice versa. To build a culture on these values, it must be explicitly communicated and consistently practiced throughout the company.

As successful businessmen and graduates of what is arguably the most elite leadership school in the world, Harvard Business School, Ray Dalio and Clayton Christensen have the right to make bold statements regarding how culture should look in a successful company. Nevertheless, it is vital to consider the importance of culture in other organizations outside of the business world to understand its overall value to organizations such as the military.

Coach John Wooden was a teacher, both on and off the basketball court. As the UCLA men’s basketball coach, Wooden became the only college basketball coach to win ten national championships. He displayed a masterful understanding of creating a winning culture, specifically while facing change and uncertainty. As a college coach, as with leaders in the Army, one’s players (or soldiers) are changing every year. A coach who is capable of winning year after year must figure out the optimal way to create a strong culture and implement it quickly.

Over the course of his distinguished career, Wooden developed what became known as his Pyramid of Success (see Figure 1.1). Similar to the pyramid structure Ray Dalio uses when discussing his “machine” (see Figure 1.2), Wooden believed that seventeen-character traits were fundamental to achieving success. In his book Wooden, he recounts a plethora of lessons that all led to his creation of the pyramid. Two of those stories stand out as fundamental to establishing a culture within an organization, largely because of the way they discuss the importance of, “cultivating meaningful relationships”, as Dalio states. (15)

First, Wooden notes the “Six Ways to Bring Out the Best in People.”(16) Of those six, three focus specifically on caring for others: “Keep courtesy and consideration of others foremost in your mind, at home and away; seek individual opportunities to offer a genuine compliment, and laugh with others, never at them.”(17) Culture is directly related to creating unity and trust, which comes through Wooden’s wisdom about bringing the best out in people. Secondly, Wooden speaks later in his book about answering the question, “Why did Wooden win?” He attributes his winning to the fact that he enjoyed hard work, and working for the benefit of others, specifically those under his coaching and tutelage.(18)

Figure 1.2 Ray Dalio's Machine Pyramid

While Dalio and Wooden share a pyramid model structure, Wooden contributes and highlights a different dynamic and defining aspect of culture by pursuing value, instead of success. While Wooden did define success by default when he created his “Pyramid of Success”, he would place significance in an individual’s life over success from external validation. His inherent definition of success, which states, “To acquire peace of mind by making the effort to become the best of which you are capable” argues this notion of significance because its definition has nothing to do with external validation, but rather becoming the best version of you that you can become.(19)

Pillars of Culture

As a new company commander, I will be faced with either establishing a healthy culture, changing a toxic culture, or possibly both. Based on the reasoning above, I believe four pillars are necessary to create a culture of mutual trust and one that will succeed.

- Clearly Defined Values

A culture cannot be faked and must align with some set of values. Dalio discusses the importance of defining a culture based on a leader’s personal values. He explains, “As the entrepreneur/builder of Bridgewater, I naturally shaped the organization to be consistent with my values and principles.” You cannot fake your values. You cannot falsify your principles. They are communicated in every action and every word you say. Basing a culture on personal values involves two implied tasks: a leader must possess personal values and they must be able to consistently exhibit them. I live by the ethos of trust, integrity, and others first, in that order. As a leader, I cannot expect my soldiers to trust me unless I am first vulnerable and trust them. Actions filled with integrity are the easiest way to portray trust, and to gain reciprocal trust from others. I know that I am truly putting others first if I am able to cultivate a culture of trust and integrity throughout the organization.

These values must also be explicitly stated. In Principles, Dalio writes about when he realized early on that his company’s culture needed to move from implicit to explicit, or rather written down and communicated instead of just silently abided by:

When Bridgewater was still a small company, the principles [culture] by which we operated were more implicit than explicit. But as more and more new people came in, I couldn’t take for granted that they would understand and preserve them. I realized that I needed to write our principles out explicitly and explain the logic behind them… I remember the precise moment when this shift occurred – it was when the number of people at Bridgewater passed sixty-seven. Up until then, I had personally chosen each employee’s holiday gift…but trying to do it that year broke my back.”(20) Dalio noticed early on in Bridgewater’s existence that if he hoped to have a company that aligned with the culture that existed at the company’s founding, he needed to state that explicitly and have it integrated at every level. The most effective way I have found to make these values stick is by constantly speaking about them and asking soldiers what the values mean to them.

- Building Purposeful Relationships

In combat arms, it is often assumed that building leader-subordinate relationships only occurs by doing hard things in the field with subordinates. I do not doubt the value of shared hardship, but this is unrealistic. Officers are paid to think and plan. We are failing our soldiers if we spend all our time with our soldiers doing their job. While officers should never order a subordinate to do something they would not do themselves, that does not mean the officer must go do the dirty work every time he commands a subordinate to do so. Building relationships can and should extend beyond shared hardship in the field. A mentor of mine, COL Everett Spain, spent every Friday as a company commander writing a handwritten note to five peers, subordinates, or superiors recognizing them for who they are or something they accomplished. This is a prime example Wooden’s belief that leaders must always seek to offer genuine compliments. People want to be recognized. At the foundation of strong relationships is an effort to recognize people for their accomplishments.

- Clearly Defined Success

Many toxic organizations define success as merely winning. Winning is important. In combat, we cannot afford to lose. But winning should be a part of success, success should not be comprised solely of winning. Healthy cultures consider people more important than things and define success as taking care of each other to accomplish a goal. This must be clearly articulated by leadership on a consistent basis.

- Recognizing a Formation’s Changing Demographics

Inherent to the Army is turnover. Soldiers and leaders rotate in and out of organizations consistently. As a company commander, one’s formation might change by fifty percent by the end of their command times. It is integral that a leader’s definition of success, explicitly stated values, and recognition of individual soldiers is consistently restated to ensure common understanding amongst a formation at all times.

Conclusion

Determining the culture a commander wants to develop is not an easy task. As I derived the aforementioned pillars, eight questions served as a guide that can be useful to other commanders as they attempt to define and build a culture:

- Does your formation have a specified culture?

- How do you define culture?

- What is your “why?

- If you have an explicit culture, do you explain that vividly somewhere to your soldiers?

- If so, what brought about the initiative to discuss culture?

- Why do you believe your team follows you?

- Is there a culture you aspire to emulate?

- Do you [the Commander] believe you are dispensable to building and maintaining your team’s success and culture?

Culture is often regarded as something that is just present within a formation, but it is also something that leaders must be purposeful about cultivating. Christensen and Dalio warn heavily against this practice of putting off creating a strong, specific company culture until later. In How Will You Measure Your Life, Christensen states specifically that one should start early in your personal life, with your family, and in your business building a culture by which you will abide. “If you want your family [business] to have a culture with a clear set of priorities for everyone to follow, then those priorities need to be proactively designed and integrated into the culture.” A strong culture is necessary to unit cohesion, and it is integral in combat. The time to build a worthy culture is not when bullets start flying, but when all is calm and relationships can be built on a firm foundation.

Captain Petersen is from Houston and most recently served as the Aide-de-Camp to the 10th Mountain DCG-S. He graduated in 2017 from the University of Delaware where he received the Alexander J. Taylor award for graduating as the top Male in the class of 2017 and completed a BA in International Relations and Mandarin, and a Master’s degree in Geography focusing on Chinese migration to Africa. In 2017, he was also selected as a Schwarzman Scholar and earned a MA in Global Affairs from Tsinghua University. Micah is the founder of Reviresco, Inc., a nonprofit which works to bridge the civilian-military divide in the US. He is also the founder of an online bowtie company, has run across the United States four times, and is an avid triathlon and marathoner. He strives to live up to Philippians 2:3 in all that he does: “In humility, consider others more significant than yourself.” Micah is also a CJO Leadership Fellow for 2022.

1. Clayton Christensen, How Will You Measure Your Life, 160.

2. Clayton Christensen, 162.

3. Clayton Christensen, 166.

4. Clayton Christensen, 169.

5. Clayton Christensen, 163.

6. Ray Dalio, 2017, Principles, New York, New York: Simon & Schuster. 299.

7. Ray Dalio, Principles, 299.

8. Ray Dalio, Principles, 303.

9. Ray Dalio, Principles, 299.

10. Ray Dalio, Principles, 304.

11. Ray Dalio, Principles, 304.

12. Ray Dalio, Principles 298.

13. Ray Dalio, Principles, 319.

14. Ray Dalio, Principles, 339.

15. Ray Dalio, Principles, 339.

16. John Wooden and Steve Jamison, 1997, Wooden: A Lifetime of Observations and Reflections on and off the Court, New York, New York: McGraw-Hill, 44.

17. John Wooden, Wooden, 44.

18. John Wooden, Wooden, 113.

19. John Wooden, Wooden, 201.

20. Ray Dalio. Principles. 304.