Company Command: Leading Change in the First 90 days

In the introductory article of the Center for Junior Officers “First 90 Days” series, the authors consider how quickly a new commander should address needed changes in his/her new company. While a gradual approach may be prudent in many situations, some situations (like the one I experienced), require a new commander to act immediately and boldly to make necessary change happen.

Symptoms of Dysfunction

My change of command date got moved up by three weeks, which reduced the commander transition window to just seven duty days. The outgoing company commander was upbeat and optimistic about the state of the company. After getting lunch following some inventories, he leaned over his desk and smirked, “I’m sure you’ve noticed that the company basically runs itself. That’ll make things really easy for you. So I wouldn’t do too much to change things.” I smiled and replied, “Good to know.”

But inside, this conversation made me uneasy. There were five days until the change of command and I didn’t feel like I had a good grasp of what was going on in the company. The outgoing commander had been sure to coordinate and conduct inventories to standard and had spent plenty of time providing me the background stories for some of the Soldiers’ disciplinary issues, administrative actions, medical reviews, etc. But I noticed that he didn’t have much to say when asked about how the company was actually run. “The First Sergeant is great – he takes care of all of that,” he said.

Quietly, I had reservations about how well the First Sergeant was “taking care of all of that.” I observed some symptoms of dysfunction:

- It seemed like Soldiers were constantly showing up late for formations and company events.

- I noticed that announcements at PT each morning included daily taskings for the company’s platoons individual Soldiers. After PT, the company’s leaders would meet to rapidly figure out how they would allocate effort to meet tasking requirements.

- Training events were not occurring or were being canceled at the last minute because of the lack of preparation or personnel support.

- I noticed that the first hour of each duty day appeared to start with a flurry of text messages as leaders worked out the who?-what?-when?-where?-why?-what uniform? questions pertinent to every event that day.

- Only about 15% of the Soldiers were present for a company awards ceremony.

- I heard frustrated exchanges from the First Sergeant’s office: “These guys act like they’ve never been in the Army before – all excuses”; “I can’t believe you don’t have people to send to the Sergeant Major’s junior enlisted training!”; “You not getting a text isn’t my fault! Get Verizon!”; “I told you we had road guard duty last week!”

Hesitant to step beyond my bounds as the not-yet-commander, I approached the First Sergeant and asked, “Top, is there a central system for how we manage events? Like an Outlook calendar, training schedule, or battle rhythm?” He replied, “Sir, to be honest, the commander probably has something like that, but I don’t have time to update that stuff day-to-day since things are changing so much. Battalion emails me or texts me stuff to get done and I make it happen.” Having spent over two years as an assistant operations officer at battalion and division levels, I knew what a well-run unit looked like. I remembered hearing, “Good units do the routine things routinely” over and over again. The company’s operations did not look like anything was routine. The company did not look like a well-run unit. It seemed like we didn’t know what was going to happen tomorrow, not even to mention next week, next month, or next quarter.

Searching for any other clue that my instinct might be accurate, I requested a copy of the company’s last command climate survey. Digging through a stack of disorganized papers in a desk drawer, the commander eventually found a heavy, stapled packet and slapped it on the desk, saying “Here ya go man. It’s pretty entertaining actually. Soldiers are just going to complain, no matter how good they have it. So I wouldn’t put too much stock in these surveys.”

That evening, I flipped through the command climate survey and a few survey sections caught my eye. First, there were a significant number of unfavorable responses in the Organizational Processes section. Additionally, the Leadership Cohesion and Exhaustion sections of the survey also displayed surprisingly negative response trends. The open-response section of the survey included numerous descriptions of a lack of timely communication, information not reaching the lowest levels of the company, and cynicism over impossibly short-notice taskings.

What quickly became apparent was that the company had a problem – and in five days, it was going to be my problem.

The commander’s role in the operations process is to Understand the problem, Visualize solutions, Describe the plan, and Direct action. Knowing this, I knew I had to quickly understand my problem.

Understanding the Problem

Examining the company’s daily operations and the other symptoms of dysfunction, I tried to identify the root cause(s). The company was missing suspenses and not accomplishing tasks to standard. Leaders were in reaction mode, scrambling to accomplish immediate requirements because the company did not have a consistent, dependable system of communication or synchronization. No one showed initiative because there was no operational predictability. But why? Like many things in a company, responsibility and accountability reside with the commander – and it was clear to me that the outgoing commander was not involved in company operations.

Armed with this understanding and anxious that the next 18-24 months in command would not be sustainable for me without major changes, I committed to fixing the company’s operations processes. Although I was hesitant to be that commander who makes large changes on Day 1, we could not wait. We were failing as a company and Soldiers were bearing the brunt of the inefficiency.

Making Change Happen

Being conscious that change isn’t easy and that I hadn’t had time to develop deep trust with the unit, I made a point of developing a clear, coherent strategy for change… Although I didn’t realize it at the time, my strategy closely followed John Kotter’s 8-step Leading Change Model:

- Create a sense of urgency. Sensitive to my role as a new commander, I did not want to advertise the outgoing commander’s shortcomings or how poorly the company was being run. I felt the urgency to change and that was enough for me, but I had to help others see the same things I did.

- Build a guiding coalition. I brought the First Sergeant and two senior NCOs into the conference room and we mapped out everything the company did on a weekly, biweekly, monthly, quarterly, and annual basis. I asked tough questions about how we made all of this happen. Once we captured recurring tasks, training, events, and requirements, we developed a company battle rhythm. Gathering these leaders to discuss operations was helpful in understanding their perspective, but it had the added benefit of helping them grasp operational inefficiencies I saw.

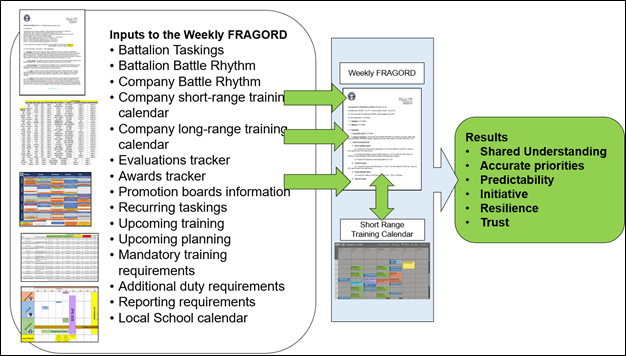

- Form a strategic vision. My vision was “Consistency = Predictability = Initiative.” Using my experience in the battalion-level operations, I knew we needed an accurate Training Calendar nested with company, battalion, and brigade battle rhythms. Even though changes always happen, I felt like we could still have 90% certainty on a week-to-week basis. We also needed a regular, dependable communication platform to put that battle rhythm into action, to disseminate taskings, and to provide operational updates with enough time for subordinates to prepare and act. I mapped battle rhythm events onto a Long Range Training Calendar and a Short Range Training Calendar. I wanted to eliminate texting as the primary means of coordination, so I developed a Weekly Fragmentary Order (FRAGORD) to describe specific operations, training requirements, and taskings 3 weeks out. The Weekly FRAGORD captured all the “ankle-biter” company and battalion taskings such as road guard, equipment turn-ins, briefings, etc. that had been killing the company. Published every week, the Weekly FRAGORD enabled leaders to continuously refine their management of personnel and priorities as they saw events approaching.

- Enlist a volunteer army. In this case, my “volunteer army” was me – I had to own my problem. After some initial trepidation at my plan, the First Sergeant shrugged “I guess we can give it a shot sir. I trust you.” (I found out later, his resistance came from expecting the process to be delegated fully to him, rather than me being personally involved.) I knew I would have to invest time and effort to put systems in place with the level of detail and precision I expected. The new calendars and orders had to be easily accessible to create shared understanding and they had to be in harmony. Mismatches in dates, times, requirements between calendars and orders would degrade the dependability of the process. I personally checked the accuracy of the order compared to the calendar. Finally, I determined that I would personally sign every order – I wanted the company to know that I was directly invested in how the company operated and the orders were accountable to me.

- Enable action by removing barriers. The biggest barrier to predictable operations was technology. Together, we briefed the company’s NCOs on how the operations process would work. We explained the new Sharepoint portal that would host the orders and calendars and we described how to request taskings for their additional duties, training, etc. to be included in the order. Finally, we explained that we, as leaders, had to be just as disciplined in communicating priorities as our Soldiers had to be in executing them. All information and taskings would be rolled into orders that would come from my desk. I eliminated last-minute texting and emails as tasking tools and established a clear expectation that changes within 48 hours of execution required a phone call. Leaders had to consult the company calendar and weekly FRAGORD to get the information they needed.

- Generate short-term wins. Over the next weeks, I noticed NCOs in the company carrying around printed copies of the Weekly FRAGORD. Leaders in the company began to identify and address conflicts two-weeks in advance, which was more than enough time to develop solutions. Soldiers stopped showing up late to events and I began to notice additional capacity to conduct training, leader development, and personal development events. Evaluations, awards, and administrative actions started coming in early as leaders began to look out toward future requirements, not just immediate needs. When I would check Soldiers’ understanding of what was happening next week, they would say “Let me check the order, sir” and they knew exactly where to go to get the information they needed. As we got more efficient, I noticed a better relationship develop between the First Sergeant and the NCOs. Out of the daily “knife-fight”, the First Sergeant was able to dedicate more time to leader development and training. The system wasn’t perfect of course. There were moments where First Sergeant and I had to put out fires on short notice. But these moments were rare. We were comfortable that we were anticipating the things we could so we would have capacity to surge to emerging missions and challenges.

- Sustain acceleration. Nothing I changed was revolutionary – the orders process, planning discipline, and calendar management – these are all routine elements of efficient operations. What was revolutionary for my company was the consistent accuracy and completeness of these systems. Over the next months, I published the Weekly FRAGORD every Wednesday evening so that company leaders could review it before Thursday morning’s company training meeting. I refined the company calendars daily to reflect changes and I coordinated with the battalion staff to understand upcoming requirements. New taskings, upcoming formations, additional duty requirements, changes to training timelines – all of these got rolled into the Weekly FRAGORD. Company leaders began to rely on their weekly 6-page burst of information and operational priorities. In one instance, I was still working to refine some taskings in the Weekly FRAGORD at the time I usually distributed the order. One of my NCOs called me to ask if I was going to be sending it that evening. Beginning to plan and synchronize, into the future, company leaders began to crave the dependable predictability the orders provided.

- Institute change. About two months after implementing the new operations process in the company, I faced my first major dilemma test. A Sergeant First Class failed to facilitate a planned inspection as part of the Organizational Inspection Program. I had published an order tasking the NCO to personally be present at the specified time and place. The inspectors arrived from brigade and no one was there to meet them. With advice from the First Sergeant and also considering this NCO’s past issues, I initiated Article 15 proceedings for “Failure to Obey an Order.” Although the punishment was superficial, we sent a clear message that leaders would be held accountable for tasks and suspenses in the order. Disciplined prioritization, execution, and initiative became part of the company’s culture. The company operations process became part of the inbrief for new arrivals and we began to expand the orders process to systemize training planning. Most surprisingly, our battalion began to be more proactive with tasks and requirements when we would ask them about events 8 or 12 weeks out. Our company system began to change the operational culture in our higher headquarters. On the next command climate survey, Soldiers reported being less exhausted and there was a significant improvement in both perceptions of communication and trust in leadership. We were doing the routine things routinely so that we could do exemplary things when necessary.

What You Can Do

The challenges you face on Day 1 of your command might not be related to inefficient operations or dysfunctional communications. You might face a challenge with an ineffective subordinate leader, command supply discipline, a climate lacking mutual respect and dignity, or a serious gap in mission readiness. Whatever challenge you face, the considerations below will help you understand the problem, generate buy-in, implement change, and build momentum.

- Ask tough questions. Do not be satisfied to hear that something is (or is not) functioning – try to observe the process, system, Soldier, or event for yourself. Seek out input from subordinates, superiors, and anyone else who might be able to see your company from a different angle.

- Understand your superiors’ priorities and intent. You must consider how much of a priority your company’s challenge(s) might be for leaders at battalion, brigade, and beyond.

- Seek buy-in from NCOs and Platoon Leaders. Commanders must understand problems, visualize options, describe solutions, then direct effort. You must be able to describe your understanding and vision to your subordinate leaders to enable them to help you build momentum. Their expertise will also help refine your ideas for feasibility and sustainability.

- Invest personally. To make change stick, you must dedicate your personal time and attention to an initiative. Leaders endorse what is important with their time and presence. So if an event is important, be there. If an inspection is important, conduct a preinspection yourself. And if an order is important, write and sign it.

- Be bold. Taking care of Soldiers is more than awards, leave, and time at home. Taking care of Soldiers means shaping the operations environment and organizational culture to enable Soldiers to accomplish their tasks, develop as professionals, and grow as people. So if you see a problem, don’t wait to fix it!

———

Major Jordan Terry is an active duty Aviation officer. He’s served in a variety of positions and has two deployments to Afghanistan. Jordan completed his MBA studies at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business in 2019, where he was a Spaulding Award recipient and concentrated his studies in Decision Sciences and Corporate Finance. Jordan also has experience as a Military Science Instructor with the Duke University Army ROTC program and is currently teaching Military Leadership at the US Military Academy at West Point.