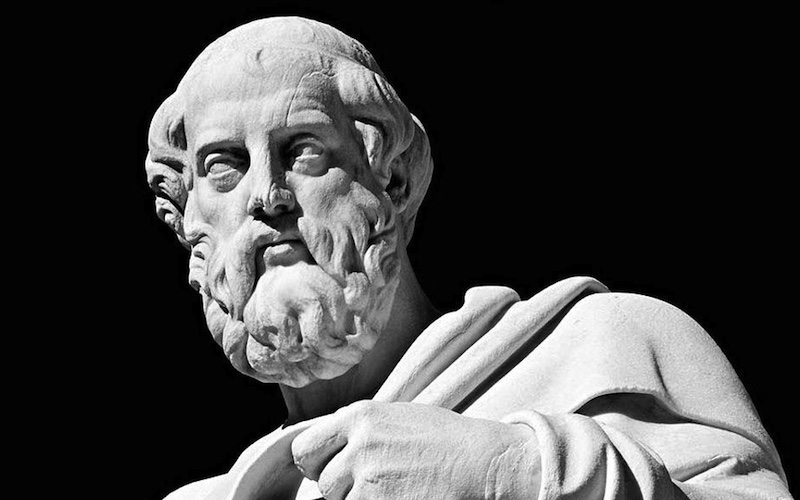

Plato’s Republic and the Profession of Arms – Cadet to Officer

In an era where the world around us is evolving faster than ever, it’s easy to get swept up in looking forward. But some of the most valuable lessons for today’s junior military leaders come from looking back. Plato’s Republic, a philosophical cornerstone of Western thought, might not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about modern Army Officership, yet still, its exploration of leadership and governance provides timeless insights for those in the profession of arms. As U.S. Army Cadets transition to Army Officers, their journey mirrors Plato’s description of the evolution from Auxiliary to Guardian—offering a unique perspective in which to understand this important transition. As someone experiencing this transition firsthand, these challenges feel particularly personal and relevant.

Plato describes Auxiliaries as the warrior class, tasked with protecting the city and embodying courage and discipline. In many ways, this mirrors the role of a cadet or newly commissioned officer, whose early career focuses on tactical execution, leading small units, and managing the day-to-day challenges of the military. These junior leaders must constantly balance the demands of their tasks with the well-being of their small element of soldiers. Similar to Plato’s Auxiliaries, this is just the starting point. The next step—becoming a Guardian—requires more. It means not just being competent but being able to recognize the good of the whole. It means grappling with the question of what it truly takes to transition from a competent leader to a committed Army Professional. As a cadet making this transition, understanding and embracing the role of a Guardian involves not only mastering skills but also stewarding the Army’s values and professional ethic.

Guardianship: “Now our guardian happens to be both a military man and a philosopher.[1]”

In Plato’s Republic, not everyone in the warrior class becomes a Guardian. It’s not a given; it requires effort, reflection, and a choice to grow. For me, the transition from cadet to Army professional isn’t about checking boxes—it’s about taking responsibility for my development and the role I’ll play in the Army’s mission.

When I reflect on my first year at West Point, my focus was narrow—just getting through the day and meeting immediate expectations. Now, as I approach this next stage, my perspective has broadened. I’ve learned that becoming a professional means more than doing what’s explicitly required of you. It’s about understanding why you’re here, aligning your actions with your values, and being honest about where you need to improve. Mentorship has been central to this process for me, and I believe it to be critical for all junior leaders in this phase of their development. Early on, I relied on practical guidance to navigate the basics. Now, I seek mentors who encourage me to think critically and challenge my assumptions. Over time, the best mentors encourage autonomy and help their mentees think critically about their decisions. This mirrors Plato’s Guardians, who grow from task-focused individuals into leaders who see the bigger picture. It’s this shift—from simply completing tasks to thinking about the bigger picture—that has shaped how I now must approach the profession.

Plato’s Guardians were lifelong learners, dedicated to improving themselves and their communities. Today, the best leaders, the Guardian-like Army Officers that I observe, adopt a similar mindset—not as an abstract ideal but as a practical approach to navigating uncertainty and leading effectively. The next step in my journey is about staying curious and committed to the profession, not settling for just meeting the expectations of a lieutenant but striving to understand my profession at a higher level. A critical part of this is acknowledging what I know and, more importantly, all that I don’t know. Recognizing my own gaps is a starting point for action—whether that means seeking out further mentorship, engaging in tough conversations with experienced non-commissioned officers, or taking the time to reflect on past decisions. For today’s rising Guardians, this means engaging with professional discourse as a practical tool to navigate uncertainty and improve decision-making in complex environments. This transition isn’t automatic—it’s about making deliberate choices to engage, grow, and lead with intention.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave: “Wherefore each of you, when his turn comes, must go down to the general underground abode, and get the habit of seeing in the dark.[2]”

One of the most enduring ideas from is the Allegory of the Cave. In it, Plato describes prisoners trapped in a cave, mistaking shadows on the wall for reality. One prisoner escapes, experiences the light of the sun—representing lived experiences that contribute to their enlightenment—and returns to the cave to share that knowledge, even at great personal cost.

For military leaders, this allegory resonates as a metaphor for growth. Early in their careers, junior leaders focus on immediate tasks. “What do I have to do today, this hour even, to meet the Commander’s guidance”—the “shadows on the wall.” As they gain experience and perspective, they move toward the “light,” developing a broader understanding of their role within the Army and the world. But the journey doesn’t end there. This transition becomes more pronounced as leaders take on roles where their influence extends beyond individual soldiers to shaping the development of future leaders.

Command, the proverbial end of when an Army Officer is considered “Junior,” provides a tangible example of this shift. In command, Army professionals are entrusted not only with accomplishing the mission, but also with developing subordinate leaders as well. This means mentoring junior officers, empowering NCOs, and fostering a culture of trust and accountability within their units. The duty to “return to the cave” reflects this responsibility. Leaders use their knowledge and experience to guide others, building cohesive teams and ensuring the organization thrives long after their tenure ends. Commanders—Guardians—are leaders of leaders. Leadership, in this sense, is not just about achieving results—it’s about investing in the next generation who will carry the profession forward.

This cycle of personal growth and returning to guide others is what makes Plato’s allegory so timeless. This cycle of growth and guiding others is a core part of Army leadership. Plato’s allegory emphasizes the shift from focusing on individual success to taking responsibility for others. As a cadet or junior officer, it’s possible to succeed by prioritizing personal performance. However, as an Army professional, it becomes your role and responsibility to develop others. In returning to the cave, leaders should be reminded that their journey is about elevating those they lead, ensuring the Army is stronger and more prepared for the challenges ahead.

Stewarding the Profession: “Isn’t a city larger than an individual man? Larger, said he.[3]”

Plato’s Guardians are not just tactical experts; they are leaders who act in the best interest of the city, balancing justice and necessity. At the heart of Republic is Plato’s vision of a just and ideal city. The health of the city, Plato argues, depends on its Guardians—leaders who combine skill with a clear understanding of justice and the common good. Similarly, the strength of the Army—and the Nation—relies on leaders who uphold the ideals of the Constitution and understand the military’s role in a democratic society. Four months out from graduation, the importance of the “health of the city” has become more and more evident to me. Military service is rooted in maintaining public trust, which requires ethical decisions, respect for civilian authority, and a commitment to the Constitution. Stewarding the profession means recognizing the Army’s role as part of the Republic, not just as a force for war. It’s about balancing the needs of the military with the expectations of the society it serves.

Ancient Greek political thought may not seem like an obvious tool for junior military leaders, but it is deeply practical. Plato reminds us that good leadership isn’t just about getting the job done—it’s about doing it in a way that reflects shared values and builds trust. Guardians must ask themselves hard questions. Did my decisions strengthen the long-term health of the unit? Am I leaving the organization stronger and more resilient than I found it? Am I upholding my oath? These questions define the transition from cadet to Army professional and, eventually, to a Guardian entrusted with leading the profession.

Looking Back to Move Forward

Plato’s Republic provides a framework for thinking about transforming into an Army professional, but it doesn’t prescribe a single path. Leadership is deeply personal, shaped by individual experiences and values. I’ve learned that it starts with reflection—asking hard questions about your character, your decisions, and the values that guide them. My most significant growth has often come from confronting my own limitations: recognizing what I don’t know, seeking the perspectives of others, and being open to change.

In a profession often focused on innovation and the next big challenge, it’s worth pausing to look back. The ideas that have stood the test of time, such as those gleaned from Plato’s Republic, remind us that leadership is as much about who we are as what we do. For those on the precipice of becoming an Army professional, the journey from Auxiliary to Guardian is not just a philosophical exercise. It’s the way we must approach how we lead, how we grow, and how we uphold our values in a constantly changing world.

[1] 525B, https://www.platonicfoundation.org/translation/republic/.

[2] Book VII, https://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.8.vii.html.

[3] 368E, https://www.platonicfoundation.org/translation/republic/.

Author Biography

Sarah Cao is a senior at the United States Military Academy and was born and raised in Plymouth, Minnesota. At West Point, Sarah studies international affairs, Chinese, and terrorism studies. Sarah has been selected as a Rhodes Scholar and will study and earn a graduate degree at the University of Oxford in the U.K.. Following her studies she will serve as a military intelligence officer.

Related Posts

Going Off Script, But Staying on Track: A Career Guide for Junior Leaders

Intro I walked into LTC Tomi King’s office as a new 2LT in his formation. We discussed all the normal talking points in that initial counseling – family, where I …

Fighting as an Enabler Leader

(U.S. Army Photo by Cpl. Tomarius Roberts, courtesy of DVIDS)Enablers provide capabilities to commanders that they either do not have on their own or do not have in sufficient quantity …

Defeating the Drone – From JMRC’s “Skynet Platoon”

If you can be seen, you can be killed—and a $7 drone might be all it takes. JMRC’s Skynet Platoon discuss their TTPs to defeat the drone.