The Cowardice and Casualties of Conflict Avoidance

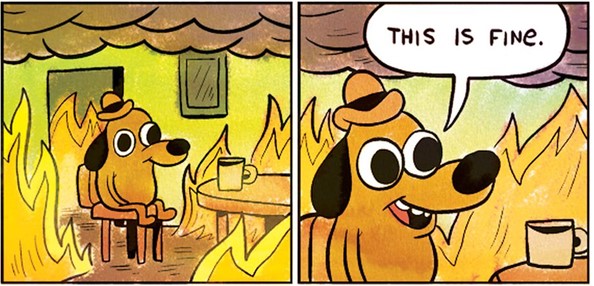

Being non-confrontational can have its upsides. Conflict-avoidant[1] people aren’t prone to burn bridges, and based on observation, they tend to strengthen teams rather than weaken them. Being non-confrontational can have serious downsides, though. One of them is hesitance to speak up when something seems off but isn’t off enough for one to be 100% sure. The same traits that help one anticipate and smooth over potential conflict can also result in silence about inappropriate behavior. That’s a no-go for leaders.

As an officer, I’m ashamed to say I learned that lesson at others’ expense. I’ve let behavior in the “gray area” go by without comment. I figured my perception of the behaviors could have been off, and I didn’t want to have awkward conversations with the behaviors’ authors over nothing. Plus, even if my perception was right, I knew the authors well enough to figure they didn’t mean it inappropriately; there wasn’t any malicious intent. They’d only acted above-board before, and so whatever I saw probably just was a one-time occurrence.

Unfortunately, that comforting internal monologue has never once proven right. I’ve learned to reject it because of the casualties left in its wake. The behaviors’ authors may not have meant their actions to be inappropriate; however, lack of bad intent didn’t protect the behaviors’ victims (or the sometimes oblivious authors) from their negative impacts.

For example, I once noticed that a junior officer seemed unusually close with an NCO in the same unit. I couldn’t tell you why I thought that; it was gut instinct. And, because I couldn’t offer concrete evidence, I didn’t approach the officer about the situation. In other contexts, the officer seemed like they weren’t as socialized to Army culture as many of their peers, so I figured they just were behind-the-curve regarding officer-NCO norms. A few months later, the officer and NCO were subject to an AR 15-6 investigation regarding the nature of their relationship.

Another example—an NCO I knew was weird to a Soldier. The NCO was instructing a cold-weather survival class, and a Soldier asked why the NCO cautioned against vigorously rubbing frostbitten hands. The NCO held out their hands as if asking for one of the Soldier’s hands, and, while answering the question, began to slowly rub the Soldier’s hand to demonstrate the proper way to warm frostbitten hands. The demonstration seemed weird, but, I figured such a demonstration (rubbing someone’s hand) probably couldn’t not seem weird. Later, the class got weird again. In explaining how to treat hypothermia, the NCO used the same Soldier in a hypothetical example. The NCO explained that if the Soldier were hypothermic, the NCO would strip the Soldier to their underwear and put them in a sleeping bag. As with the first incident, the NCO seemed wholly focused on instructing and oblivious to the eyebrows that shot up in the room. After the class, I did not pull the NCO aside. I figured they were socially unaware instead of “harass-y.” Six months later, the NCO was the subject of an AR 15-6 investigation for possible sexual harassment.

I don’t know the details or outcomes of either of these investigations. I don’t know if my speaking-up in either instance would have changed anything. But, I know it might have. I also know it was not wisdom that kept my mouth shut, but the desire to avoid potential conflict and personal discomfort—which, if I’m honest with myself, is cowardice. I put my comfort ahead of the well-being of potential future victims of inappropriate behavior. I put my comfort ahead of the well-being of the potentially oblivious authors of the inappropriate behavior. Both the officer and NCO might have changed their behavior if I had said something. And the Soldier(s) on the receiving end of the other NCO’s behavior might have been spared from it. I denied them that chance out of personal fear.

If you’re someone like me, I have three pieces of advice.

- First, listen to the initial, internal voice that says, “That person’s behavior seems inappropriate” and talk to the person. If the person is oblivious to how their actions could be perceived, they probably will appreciate that you care enough to pull them aside. Either way, we owe it to Soldiers on the receiving end of the behavior to speak up.

- Second, ignore the fearful, self-doubting inner voice that offers thirty-seven reasons why your perception is off and suggests you wait and see for more clear evidence.

- Third, ask a trusted mentor if still in doubt. You can run the scenario past them and ask them for a sanity check.

If you’re not someone like me, be aware there are people like me in your formations and coach us. An easy way to recognize us (at least some of us) is to identify your people-pleasers; odds are we’re conflict avoidant. That’s not always a bad thing—not stepping on toes can often be helpful. Being gagged by fear is not, though. If you can, do some preventative maintenance during counseling. Help us learn to speak up before the cost of our reticence is borne by others.

———

[1] This article’s scope is the downside of non-confrontation when motivated by fear; for information on conflict avoidance’s strengths and weaknesses as a mode of conflict resolution, please see: https://www.uscg.mil/Portals/0/seniorleadership/chaplain/5%20Types%20of%20Conflict%20Styles.pdf?ver=2020-01-16-150312-237

———

MJ Cantrell is an active-duty captain pursuing a PhD in political science at Arizona State University. CPT Cantrell commissioned from the US Military Academy at West Point, and received a master’s degree from the War Studies Dept of King’s College, London. She is a Center for Junior Officers 2021 Leadership Fellow.

Related Posts

Fighting as an Enabler Leader

(U.S. Army Photo by Cpl. Tomarius Roberts, courtesy of DVIDS)Enablers provide capabilities to commanders that they either do not have on their own or do not have in sufficient quantity …

Defeating the Drone – From JMRC’s “Skynet Platoon”

If you can be seen, you can be killed—and a $7 drone might be all it takes. JMRC’s Skynet Platoon discuss their TTPs to defeat the drone.

3 Deployments Before Captain: Reflections From Down Range

Deployments challenge junior officers beyond their primary duties, often demanding adaptability, wellness management, proactive leadership, and moral integrity maintenance.