The Secret to Success in Professional Military Education

It was a conversation I had several times as an assistant professor at the United States Military Academy (USMA). First-class cadets, mere months or even weeks from graduating, would approach me with questions on how to succeed at the Basic Officer Leaders Course (BOLC). These cadets, having read my instructor biography, knew that I had performed well in my professional military education (PME) courses and wanted to know my “secret to success.” Unfortunately, I was never able to provide these cadets with the comprehensive answer. The fact is that I never went into one of these courses with the intent of graduating at the head of the class, let alone with a plan to do so. Rather, in most cases, I simply hoped to graduate alongside my classmates. As my time at West Point came to an end, I finally found the time to look back at the past 18 years and deliberately reflect on what made me successful in my PME courses. Through that reflection, I was able to identify several common characteristics, some conceptual and some more practical, that I believe contributed to my success. I share these now in hopes that young officers can apply them to succeed in their PME, both for themselves and the young men and women they will lead throughout their careers.

Attitude is Everything. Like so many things in life, when it comes to PME, attitude is everything. Officers must approach PME with the right mindset. They must recognize that PME represents both a tremendous opportunity as well as a professional responsibility. They must check their egos at the door and acknowledge that, regardless of their past experience or commissioning source, they are not omniscient. All officers have significant room to learn and develop as members of the profession. Only after an officer acknowledges and accepts these truths can he/she fully commit to his/her PME experience.

It is an Opportunity. Officers need to realize that PME is not something to simply “get through.” Instead, it represents a tremendous opportunity. Few professions provide such structured developmental opportunities where members can unplug entirely from work for several months or even a year to learn and grow as a member of the profession. While all officers have the opportunity to attend BOLC and the Captains Career Course (CCC), PME beyond these courses becomes increasingly selective. The Army selects approximately 50% of newly promoted majors to attend resident intermediate-level education (ILE). The selection rate for lieutenant colonels and colonels to attend a senior service college (SSC) is even lower. Officers who acknowledge and accept PME as a tremendous opportunity are less likely to squander it. Rather than taking the “check the block” approach, these motivated officers will seek to get the most from their PME experience. Approaching PME with this positive attitude will greatly contribute to an officer’s performance by providing the necessary motivation to overcome challenges and push him/her to excel.

It is a Responsibility. While a tremendous opportunity, PME also represents a tremendous responsibility. Unfortunately, many officers selfishly view these courses as completely distinct from their future obligations. As such, many fail to take their personal development seriously. They may fail to complete assigned readings, put forth minimal effort on practical exercises, or play on their electronic devices during class. These shortsighted officers believe they are not hurting anyone but themselves by doing the bare minimum to pass. That is simply not the case. Ultimately, by failing to push themselves to their full potential during PME, they are not only failing themselves but also their future subordinates, peers, and superiors alike. As Army professionals, we have a responsibility to become experts in our craft and stewards of the profession. Officers who do not take their PME seriously fail to live up to these expectations and, unfortunately, it is often the soldiers they lead who pay the price.

Be Humble. To fully embrace PME as both an opportunity and an obligation, an officer must be humble. At every course I attended throughout my career, there were always officers that acted as if they already knew all the answers, as if they had nothing to gain and the course was beneath them. This can be a considerable obstacle for young West Point graduates who, as noted in Jordan Swain and James Watson’s article, “West Point Lieutenants Lack Self Awareness,” often graduate with inflated opinions of themselves. The haughtiness of the West Point graduates was clear to me as a young second lieutenant at the Armor Officer Basic Course (OBC). Their inflated egos not only hindered their ability to learn from officers from other commissioning sources but also from their NCO instructors, both of whom the “Old Grads” seemed to view as beneath them. Similarly, at the Maneuver CCC, I remember fellow captains with one or two combat deployments exhibiting “been there, done that” attitudes that prevented them from approaching the course with open and eager minds. No matter an officer’s knowledge or experience, he/she should approach PME with humility; a humble mind drives a thirst for knowledge and development.

It Requires a Commitment. Succeeding at PME requires commitment. However, to truly excel, an officer must make PME their number one priority. Competing requirements can make this a significant challenge for some officers. I remember many West Point graduates exercising their newfound freedom at OBC to go drinking every night. These lieutenants appeared more focused on having a good time than their professional education and development. At CCC and the Command and General Staff College (CGSC), many officers, mentally and physically exhausted from years of combat deployments, understandably chose to use their time at PME to reconnect with family and “take a knee” from operational requirements. Ultimately, it is each individual officer’s choice as to how they prioritize PME. However, those wanting to earn top marks, they must make PME the top priority and be willing to make sacrifices accordingly. It was this commitment to PME that enabled the more practical methods that contributed to my success.

Prepare for PME. Success at PME begins long before the first day of class. Just like any other operation, success requires proper planning and preparation. Officers should take advantage of the time leading up to PME, whether it is prior to a permanent change of station or while “snowbirding,” to set conditions for their success. A few months in advance, officers should begin reviewing notes and material from their previous PME. For example, prior to attending CCC, it is advantageous to review notes from BOLC. Prior to attending ILE, officers should review their CCC materials. This can help shore up an officer’s foundational knowledge prior to PME, allowing them to focus on new material. Next, officers should seek out course materials for their upcoming PME to help get a jump start on the course. Simply skimming through the readings and presentations in advance can provide a significant advantage in comprehending the information during the course. Officers can also begin chipping away at course requirements. For example, the battle analysis paper was a long-standing requirement at CCC and represented the course’s longest writing assignment. Knowing this, I selected a battle, did my research, and outlined my thoughts all before I even started CCC. This saved me a considerable amount of time during the course that I could refocus on other course content.

Set Conditions. Preparing for PME goes beyond academics. Officers should do their best to eliminate distractions and set conditions for success prior to their first day. Officers should ensure that their annual requirements, including Army Regulation 350-1 training and medical readiness, are not only current but will not expire during PME. It is also important to show up to PME physically fit and healthy. Contrary to many officers’ beliefs, PME is not the best time to lose weight, get in shape, or have surgery. It can be extremely challenging just to maintain one’s level of physical fitness based on course schedules and out-of-class requirements. Strict policies regarding absences can also make it difficult to schedule appointments. Medical procedures or conditions that require convalescent leave may result in a recycle or even a drop from the course.

Get Your Home in Order. It is important that officers set conditions at home prior to beginning PME. Officers should backwards plan and arrive far enough in advance to get established prior to the first day of class. Upon arriving, it is important to spend some time becoming familiar with the area and determining where to live. Living on or near post provides distinct advantages regarding time management, affording more time for study, fitness, family, and rest than those commuting a long distance from a nicer off-post community. Officers should plan moves and household goods deliveries with sufficient time to get unpacked and settled. When setting up a new home, it is essential to have a dedicated space void of distractions to work and study, such as a home office. For those with families, it is important to manage expectations. It is important for family members to be aware that although their spouse, father, or mother may be home, they may still have a significant amount of work to do; out-of-class requirements for PME are substantial.

Establish Good Study Habits. Transitioning into an academic environment can present a challenge for officers of all ranks. Young lieutenants may find it challenging to dive right back into an academic mindset after graduating college, whereas senior officers, several years removed from academia, many need to reestablish study habits. For me, establishing a routine was critical to maintaining good study habits. While my exact routine varied from course to course, generally the overall pattern remained largely the same. I would conduct physical training each morning. After personal hygiene and breakfast, I would briefly review my notes from the previous evening’s readings or assignments before class. After class was done for the day, I would take time to deliberately review that day’s content. After taking a break for a few hours to decompress, do some PT, and have dinner, I would settle into my designated study area to begin completing any reading or assignments for the next day. I always kept this area free of distractions, such as television, cell phones, and social media. Before concluding my studies for the day, I would always take one final look over my notes and prepare questions for any material I did not fully comprehend.

Get Organized. While every officer’s approach to studying may vary, organization should be the common denominator. Officers attending PME are required to balance numerous out-of-class requirements including readings, presentations, and writing assignments. For some courses, rotational leadership positions, organized physical training, and extended field exercises add additional layers of complexity to the calendar. To excel, officers must effectively forecast and prioritize requirements and balance their time accordingly. This requires both long-range and short-range planning. For example, at the beginning of each course, I would review requirements and note all major events on my calendar, including papers, briefings, examinations, field problems, and other unique requirements. This helped ensure that major events never caught me by surprise and helped facilitate backward planning. Each weekend I would conduct my short-range planning, forecasting all requirements for the coming week day by day in significant detail, allowing me to identify potential points of friction and plan accordingly. During the work week, I would review my calendar multiple times a day to stay abreast of requirements and work ahead when possible, such as during short breaks between lessons or over lunch. This detailed planning gave me a significant advantage over my classmates who elected to take a day-to-day approach to PME. Many of these officers lived by the adage, “If you wait until the last minute, it only takes a minute,” and it showed in their performance.

Leverage Downtime. Time is perhaps an officer’s most precious resource during PME. Those striving to excel must seek to maximize their time outside of class. This includes multitasking and taking advantage of weekends and holidays. Physical training and daily commutes present excellent opportunities for multitasking. Several reading requirements, including military publications, are now available as audiobooks. While not for the faint of heart, officers can also make voice recordings of their study materials to use as audio flashcards. Although not the most riveting material, completing reading assignments or studying by audio while doing cardio, driving, or performing chores around the house can buy back a considerable amount of time. Weekends and holidays offer the most potential. While these short breaks provide a great opportunity to unwind and relax, officers hoping to excel will take advantage of this downtime to chip away at long-range requirements and prepare themselves for the coming week.

Do the Reading. As an assistant professor at West Point, it never failed to surprise me how many cadets consciously chose to “assume risk” rather than do the assigned reading for class. While some cadets may have been able to skate by, it was exceptionally disappointing to learn that this was the approach that so many of America’s “best and brightest” took toward their education. Unfortunately, that same indolence exists in officers at PME, epitomized by the popular saying, “It’s only a lot of reading if you do it.” While many officers still manage to complete PME in this manner, those seeking to excel need to do the reading, take notes, and participate in class. These simple actions, which are every officer’s responsibility during PME, will help set studious officers apart from their apathetic classmates in more ways than just their academic evaluation reports (AERs).

Learn From Your Classmates. Instructors are not the only people from whom officers can learn from during PME. Officers can learn a great deal from their classmates if so inclined. Each officer brings unique knowledge, skills, and experiences into the classroom. Unfortunately, some officers fail to capitalize on the knowledge and experience of their peers. For example, during the Special Forces Qualification Course, all but two of the captains had combat experience. Many of my peers dismissed these captains based on their “slick sleeves.” However, in reality, these two captains had a lot to contribute. Having served their lieutenant years as opposing force (OPFOR) platoon leaders at the National Training Center and Joint Readiness Center, these two officers possessed several years of training and experience in small unit tactics and guerrilla warfare. Those of us willing to learn from the experiences of our “slick-sleeved” classmates benefited immensely.

Help Your Classmates. Officers in a position to do so should seek out opportunities to assist their fellow classmates. Aiding others can help an officer develop mastery of the subject matter. While attending CGSC at Fort Leavenworth, I spent a considerable amount of time assisting my classmates from non-combat arms branches with assignments and exercises related to tactics and strategy. Beyond the sense of personal and professional fulfillment, I felt from helping my fellow officers, talking them through different concepts, and answering their questions forced me to rethink and articulate the subject matter, ultimately strengthening my knowledge of the topics.

PME is Enduring. Officers should remember that PME is enduring. Officers cannot afford to simply “brain dump” knowledge immediately following an examination, practical exercise, or even graduation. While formal PME may be limited to the months spent at BOLC, CCC, ILE, and SSC, each officer has a responsibility to continue their own professional military education and development beyond the confines of formal schooling. Officers must not only retain this knowledge but should continue to build upon it through its practical application. Taking the time to deliberately reflect on and make the connections between schoolhouse knowledge and real-world application truly makes an officer an expert in his/her craft. As such, officers should keep and periodically review their PME materials. A technique I employed was to maintain a three-ring binder with all of the unclassified study guides I used throughout my career. Every week I would pick one or two study guides and dedicate ten or fifteen minutes to reviewing the material. Beyond just refreshing my memory, the information would often take on new meaning as I would reflect on it with new experiences, ultimately contributing to a deeper understanding of the material.

In conclusion, there are numerous factors that contribute to an officer’s success at PME. To me, the most important quality is taking one’s education and development as an Army officer seriously. In every course I attended, there were officers that were likely more capable than I was, but very few took their responsibility as seriously as I did. By approaching PME with the right attitude and commitment, I repeatedly found myself at the head of the class on graduation day. However, infinitely more important than graduation day honors or high marks on an AER were the knowledge and experience I took away from those courses and applied to operational assignments throughout my career.

Lieutenant Colonel Ken Segelhorst graduated number one or two in every AER-generating course he attended throughout his career. He was the Distinguished Honor Graduate of the Armor Officer Basic Course, Honor Graduate of the Maneuver Captains Career Course (Infantry), Distinguished Honor Graduate of the Special Forces Qualification Course, Honor Graduate of the Information Operations Qualification Course, and a Distinguished Graduate of the Command and General Staff Officer Course. He is currently assigned to Headquarters, U.S. Special Operations Command, MacDill Air Force Base. He previously served as an assistant professor and the course director for MX400: Officership, at the United States Military Academy at West Point. LinkedIn

The author would like to thank his wife, CPT Heather Segelhorst, for her support and assistance in preparing this article for publication with CJO.

Related Posts

Authentic Mentorship – Buzzwords to Breakthroughs

Forget quick fixes—authentic mentorship demands vulnerability, patience, and trust, pushing mentors and mentees beyond comfort zones toward true growth.

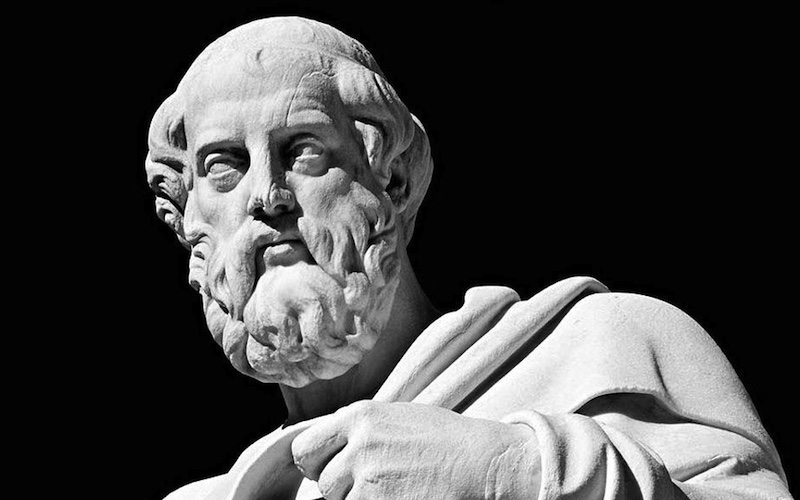

Plato’s Republic and the Profession of Arms – Cadet to Officer

A USMA Senior Cadet and Rhodes Scholar, reflects on her upcoming transition from Cadet to Officer through the lens of Plato’s Republic.

In SOF – Relationships Reign Supreme

A Civil Affairs officer reflects on a recent deployment to Syria and how the relationships he built and maintained led to his success.