Three Things to Make You Good at Any Job

Advice on leadership can take many forms and come from many different places. Some are obvious and direct, like teachers, coaches, peers, and mentors. Others are indirect: historical figures, books, or TED talks. And some truly come out of left-field. These are the random tidbits of knowledge gleaned from everyday life when you least expect it. They’re often harder to come by, but they can have an outsized impact on us if we’re willing to listen.

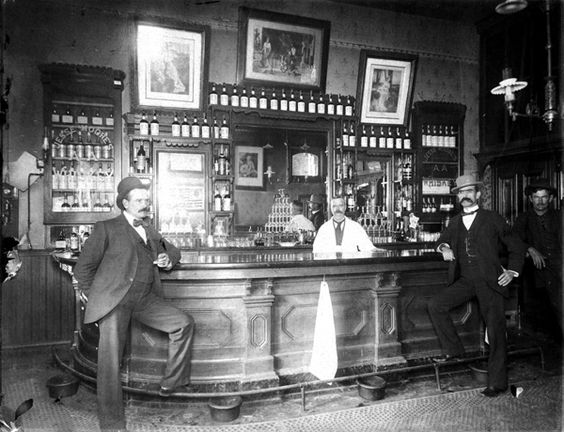

For me, one such lesson came in a place that could not be more removed from the Army: a wine bar in San Francisco, CA.

My friend and I had spent all day walking the city and were looking for a drink before dinner. We saw a place that looked promising and ducked in to see what they had. As we slid onto our stools, the bartender – let’s call him Bernard – came down the bar towards us.

Bernard was one of those guys who can talk to anyone — a useful skill in his line of work. The opening, “How we doin’ today folks?” segued seamlessly into the, “Where you visitin’ from?” When we said we were local, his well-practiced banter became more genuine. In minutes we were talking like old friends.

So, “what do you do for work,” Bernard asked. Both of us had just started new jobs, we told him.

At this point, Bernard shared with us his three keys to success at any job:

- Be on time

- Do good work

- Don’t be a jerk.

As he put it, doing two out of three makes you good; doing all three makes you great.

We duly laughed at his “advice,” but in the years since, I’ve come to appreciate the wisdom in his words. I still find myself reflecting on how those three rules can help someone be successful in the Army.

Be on Time

There are numerous hit times, deadlines, due dates, and time hacks leaders must meet. Being chronically late to meetings or constantly missing deadlines is a sign of poor time management. It shows your Soldiers and your Commanders that you can’t be relied on when the chips are down. Failing to manage your time wisely guarantees you will drop the ball on something. How you manage your time is up to you. There are as many methods as there are people. Whatever system or method you use needs to have a few basic criteria.

First, capture all of your obligations accurately and reliably. Do it on your phone, in a notebook, or anything else that you will always have on you. The total tonnage of what platoon and company leaders have to get done is staggering. There is simply too much information coming at you to remember everything, so start writing things down.

Second, ruthlessly prioritize. How you do that is a delicate balance between Soldier welfare, the mission, your priorities, your commander’s priorities, etc. Part of prioritizing well is having good communication up, down, left, and right. You need to understand where tasks fit into the bigger picture to understand their importance.

Third, learn to say no. The harsh reality is there’s too much for us to do, and we can’t be in two places at once. It’s ok to say no to things. Do it with tact, respect, and a clear reason why. You’ll get overruled sometimes (many times probably!), but blindly saying yes to everything is a surefire way to lose any semblance of control over your time.

Do Good Work

We all want to be engaged, thoughtful, knowledgeable leaders, but there are several implied tasks hidden within this desire. For one, quality work takes time (see how these fit together?). You have to make time to study, practice, and learn about your job, your team, and the Army.

The fundamental implied task here is READ EVERYTHING. Don’t know the products your staff section is responsible for during MDMP? Read doctrine. Don’t know how to request ammo for a range? Grab the unit SOP. See a Soldier who’s a bit of a loner reading a sci-fi novel? Skim a copy and use it to start a conversation. It is naïve to think all — even most — answers can be found in a book or manual. What you will find though, is a starting point. Every problem we face as junior leaders, someone else almost certainly faced a version of it before. Chances are, someone wrote down how they handled it, too.

But what if it isn’t written down? What if your time constraints prevent you from reading what you need? Execute the next implied task: ask for help. Do not ask for the answer and forget it, ask questions that help you understand why the answer is what it is. Use it as a chance to learn how to do something new. Do this with everyone, not just your superiors and senior NCOs, but with Joe. If you don’t know how to PMCS a vehicle, you can (and should) read the TM. However, if you need it done in the next 30 minutes, a more efficient way is to ask one of your Specialists who does it every day. Work with them, ask them questions, and get your hands dirty. You’ll learn faster and they’ll appreciate that you did it with them rather than tell them to do it and walk off.

Finally, take pride in your work. Regardless of the task assigned, do it to the best of your ability. There are thousands of assignments in the Army and they all need to be done well to accomplish the mission. You will do many of them. Some will be hard. Some will misuse your skills. Some will just suck – but none will ever be beneath you. The Army is a team sport. Leaders are also team builders, and they build their teams out of those who care about the quality of their work.

Don’t Be a Jerk

No one wants to work with or for a jerk. A bad attitude towards subordinates, peers, or higher leaders can quickly turn a command climate hostile, toxic, or both. Have empathy and treat everyone with respect. You don’t have to like everyone – in fact, you almost certainly won’t – but you must always engage people in a professional, civil, and (dare I say) kind manner. Invariably, we all lose our cool at some point – everyone gets chewed out eventually…and probably chews someone else out too. Don’t let that be your default setting.

One of the oft-shared nuggets of wisdom is that leaders set the tone for their organization; that a unit takes on its leader’s personality. I was skeptical of this for many years until I witnessed it up close. Soldiers I knew well were detailed from my unit to another staff section. Their day-to-day leadership shifted to a different set of officers and NCOs from outside our company. Within a matter of weeks, the tone changed. Morale suffered, personal drama and professional disagreements rippled through the element, and several Soldiers were involved in incidents requiring significant disciplinary action after as little as six months.

There were many factors to these problems. Several stemmed from individuals’ actions beyond the power of any leader to control. However, the general attitude of leadership was negative. This bred a contentious, even adversarial relationship, with other sections. Such an attitude is infectious. Your Soldiers will follow your lead, make sure it’s a positive one.

How to Implement These Rules

These simple rules shouldn’t surprise anyone. Yet, it’s astounding how so many of us forget them so often. When a project or training event starts to cause stress it’s easy to be caught up in the moment and forget to review timelines, let quality control slip, or just start snapping at people. In those times, use these steps like you would any other checklist. Take a minute or two to think through each step. Doing so will help you self-correct and improve the event’s quality…or at least learn for next time.

The Army builds in tools that make a checklist approach work on a macro level as well. Command climate surveys are often treated as just another thing to click through. Don’t let that be the case. Impart on your Soldiers how important these are and follow through on correcting the issues they identify. AAR’s, counseling sessions, and just walking around can be used in a similar manner. Look at the last five events your unit conducted, what are the commonly recommended improvements? Does your platoon sergeant consistently bring up the same issue during your quarterly counseling? Do you hear talk in the motor pool about the same gripes? Target these things.

Conclusion

Junior Army leaders often listen to their Commanders or General Officers, furiously scribbling down their advice and words of wisdom, with the goal of becoming better leaders. Some read voraciously or listen to podcasts led by celebrity CEO’s and leadership gurus. Both can be good sources for leadership development, but they’re not the only places we can gain insight. Wisdom can come from the most unexpected places — like a bar.

Be on time, do good work, and don’t be a jerk. To this day, it is certainly the best advice I’ve ever received in a bar – and the wine was pretty good too.

———

Lucas Thoma is a Military Intelligence officer in the California National Guard. He’s been a platoon leader, company commander, and staff officer. He’s a foodie, craft beer nerd, and an actual nerd.