West Point Lieutenants Lack Self-Awareness

Do we have your attention? If you’re a West Point graduate, maybe you bristled at the headline. If you received your commission from another source, maybe you nodded and smiled. Why did we choose this title? Well, because it’s true.

Hear us out. Most lieutenants are lacking in self-awareness. In a 2020 study of new lieutenants and warrant officers fresh out of their basic course, there was a mismatch between the officers’ self-reported level of competence and the level of competence reported by more senior leaders who worked with them. Lieutenants leaving BOLC-B tended to report high levels of perceived individual competence in human dimensions like “ability to actively engage with Soldiers” or “ability to solve problems when there is no right answer.” Meanwhile, senior military leaders who worked with Lieutenants tended to rate their actual competencies in the human dimension with much less enthusiasm. This difference was greatest among West Point Lieutenants, as they reported the highest comparative levels of confidence in their preparation for the challenges ahead. However, after observing their actions in operational units, only 30% of the senior leaders surveyed agreed that USMA graduate lieutenants were “best prepared”. Why does this matter you may ask? Well, this difference between self- and other- evaluation suggests a lack of self-awareness.

What is Self-Awareness

The concept of self-awareness is a critical part of cultivating effective leadership, and a skill that great philosophers have sought since the time of the ancient Greeks (most readily envisaged in our culture by the phrase “know thyself” attributed to Plato, inscribed on the temple of Apollo At Delphi). At its most basic, self-awareness is an accurate view of one’s strengths and weaknesses. It also involves understanding one’s thoughts and emotions and having a firm and accurate sense of self. Its importance is stressed throughout leadership and leader development literature with self-awareness being linked to being confident, creative, and an effective communicator. Self-awareness is also part of many conceptualizations of emotional intelligence, humility, resilience, and authentic leadership. The list goes on…really….it goes on and on and on. We don’t want to provide an exhaustive literature review here, but we would like to highlight just a few more outcomes associated with high levels of self-awareness that should be of interest to any Army leader – self-awareness has been linked to ethical behavior, sound decision making, and employee satisfaction and motivation. Given some of the challenges the Army is currently facing, we submit that leader self-awareness is something all lieutenants (and you) should take a keen interest in.

Self-Awareness Lowest in West Point LTs

In the opening paragraph, we mentioned West Pointers, which is probably why a number of you are still reading. The 2020 TRADOC Research and Analysis Directorate study, mentioned above, reported that the largest gap between self-assessment and the assessment provided by others was seen in West Point graduates, followed by ROTC and direct commissioned officers, while OCS graduates tended to rate themselves most closely to the assessments offered by their superiors.

Why do you think this is? Perhaps the different experiences provided by the different commissioning sources vary in how effectively they contribute to their students’ self-awareness. It could be that West Point cadets are told they are the best and are given a false sense of confidence, while those from OCS may be treated differently and provided different feedback that contributes to a more accurate view of their capabilities. It is also possible that the nature of West Point as a total institution inhibits the average cadet’s ability to gain self-awareness in social settings more akin to those they will face as a commissioned officer.

Age tends to correlate with self-awareness. With OCS graduates tending to be a few years older than ROTC and West Point Cadets, they may indeed possess a greater level of self-awareness.

Biases on the part of senior leaders could also play a role here, as many make assumptions about West Point graduates and “Mustangs” (you know the stereotypes).

Ultimately, we submit that is does not matter where you commissioned from. All lieutenants tended to rate themselves higher across all measured dimensions when compared to the assessment provided by their superiors. That means ALL LIEUTENANTS should be concerned with improving their level of self-awareness. Quick note- self-awareness isn’t just an issue for LTs. In one study, 95% of people reported they are self-aware when only 10 to 15% actually were.

Don’t Be the Overconfident, Incompetent LT

We mentioned earlier a handful of the many positive outcomes associated with high levels of self-awareness, with several of these positive outcomes being extremely relevant for some of the issues Army leaders are currently facing. If those don’t resonate with you, ask yourself this question instead – do you want to be an overly confident idiot? What do we mean by this?

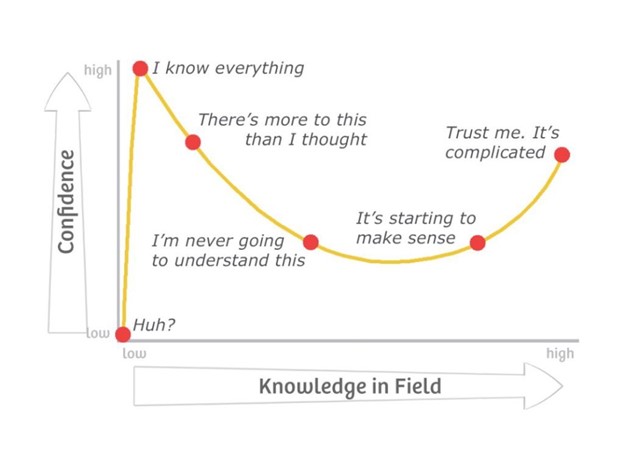

Let’s take a minute and explain something known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect- and if you haven’t jumped on the bandwagon already, we think you’ll come around to our way of thinking and embrace the notion of wanting to improve your level of self-awareness.

Perhaps the most worrisome of the many self-awareness blind spots is the famous Dunning Kreuger effect; where the lowest performing members of a group are unable to recognize that they are “among the worst.” Meanwhile, their subordinates, peers, superiors, and even outside observers can identify their obviously poor performance. In other words, the least competent think they’re the best and are overly confident– they literally don’t know what they don’t know. On the other end of the spectrum are the truly competent – but their perception of themselves is informed by an accurate understanding of knowledge and skills. The simplified graphic we’ve inserted can help clarify.

Ultimately, you don’t want to fall victim to your own lack of self-awareness. The results can be devastating and, according to some research, can cut a team’s chances of success in half, with other outcomes including colleagues’ increased stress, decreased motivation, and a greater likelihood of leaving one’s job. These are things Army leaders do NOT want to happen in their units!

So What Can You Do?

There are a number of things you can do to improve your self-awareness

- Learn to be Vulnerable. Be vulnerable and authentic. Making the decision to show your truthful, authentic self to others can incredibly intimidating. Fear of looking incompetent or of rejection can be powerful. This goes against our natural protective instincts, and it is a learned skill that must be practiced to gain (and maintain) proficiency. In fact, Bob Kegan and Lisa Lahey’s Immunity to Change asserts that efforts to conceal weaknesses from others is the single largest dynamic that costs organizations productivity. In order to start on a path of greater self-awareness, you must learn to let those around you see who you are, not merely the version you want them to see. If you are interested in learning more about this topic, we recommend checking out Brene Brown’s fantastic book, Dare to Lead (as well as her TED talk at the hyperlink above).

- Find a Mentor. Engage with a mentor who will give you honest feedback, and who can help you develop your self-awareness. Not all mentors are built alike, and not all mentors will be able to help you grow in all areas. If self-awareness is something that you find yourself lacking in, then you need a mentor who can help you in this specific area. To learn more about mentorship, selecting a mentor, and other considerations, check out the Army Officer’s Guide to Mentoring which is available through the Center for Junior Officers website.

- Welcome Feedback. Foster an environment where respectful criticism is encouraged in your unit. Seek feedback from those around you, develop plans cooperatively with your peers and subordinates, and make the deliberate decision to consider thoughtfully all ideas from all sources. Respectful criticism does not have to be as formal as the MSAF 360; it can be as simple as asking your subordinates and peers “what have I been getting right and wrong over the last few months?” Push them for specifics; anecdotes are powerful tools and can help you recall your own thinking in those moments and improve your retention of those criticisms. We posted an article here on “How Not to Suck at Gathering Feedback as an Army Leader.”

- Budget Time to Reflect. Feedback without reflection isn’t useful. Make a conscious decision about when and how you will reflect upon the observations people provide you. Deliberate reflection drives character growth, and most Army leaders do not create space for this valuable activity. One of the authors of this piece finds peace in working with his hands, and deliberately spends time thinking about topics during this time. You may find that journaling or another avenue that works for you. Try different things but find something that helps you reflect. You might consider the Army’s new Project Athena (if you do, let us know your thoughts!)

- Practice Humility. Humility is a proven character trait of effective leaders. With its addition into Army doctrine, every leader should take stock of their own humility, and reflect upon its importance. You can read a CJO article on developing humility if you’re interested in learning more.

Conclusion

Overconfidence is a problem that isn’t limited to West Point LTs; it can (and does) affect all of us. Most importantly, the consequences can hurt your ability to build strong performing teams, care for your Soldiers, and accomplish your mission. Self-awareness is an important component of being an effective leader, and you ignore growth at your own risk. Regardless of your commissioning source (or your rank), you should ask yourself “am I self-aware?”

As a final point, if you needed further evidence of the importance of self-awareness, studies of Naval Officers have shown that organizations led by more self-aware leaders outperform their peers. Now we know it’s the Navy, but the results of the study are still applicable and useful ; )

———

Lieutenant Colonel Jordon Swain is the Director of the Center for Junior Officers and has course directed the core Leadership course at West Point. He holds a Ph.D. in Organizations and Management from Yale University and an MBA from the Wharton School. LTC Swain has published on multiple topics related to leader development including leader humility, mentoring, and humor’s impact on leadership effectiveness. It’s starting to make sense to him now…he thinks…maybe.

Captain James Watson is the Operations Officer for the Center for Junior Officers. He is a Logistics Officer, holds a Master’s in Organizational Psychology from Teacher’s College, Columbia University, and is a 2013 graduate of the United States Military Academy. He too was an overconfident idiot not too long ago.